Last year, the IIHS published their first list of used car recommendations for teenagers, and I explained here why the list was less helpful to most parents than it could have been. While well-meant, the article was tone-deaf to the economic realities of the country at best and destructive by enabling misconceptions and vehicular arms races at worst.

Last year, the IIHS published their first list of used car recommendations for teenagers, and I explained here why the list was less helpful to most parents than it could have been. While well-meant, the article was tone-deaf to the economic realities of the country at best and destructive by enabling misconceptions and vehicular arms races at worst.

Strong words, I know. Let’s look at that a bit more closely, and then I’ll have my recommendations for safe, affordable used cars, SUVs, minivans, and pickup trucks for teen drivers, based on vehicle availability in 2016.

Why was the previous IIHS analysis of safe teen vehicles a poor one?

The main reason for its relative unhelpfulnesss was because a.) it ignored the realities of how much money parents were actually spending on vehicles for their teenage drivers, b.) it misled readers into believing that all teenage drivers were the most dangerous (they’re not), and entirely avoided the greater issue that teenage male drivers are the most dangerous on the road, and c.) it encouraged a vehicular arms race by telling parents to buy large and heavy vehicles for the least experienced drivers on the road.

So if there were so many issues with the 2014 article, why am I looking at their 2015 report? Well, the IIHS does provide a lot of good information on crashworthiness, and I was hopeful they would provide far more useful, accurate, and relevant information to parents this year on safe and budget-friendly car choices for adolescent drivers. Let’s see how they did.

1. How much are parents spending on cars for their teenagers, and do IIHS recommendations address these amounts?

Last year in 2014, the IIHS reported the median amount spent by parents on vehicles for teens was $5,300. Adjusting for inflation, this yields a sum of $5,327 in 2015. The IIHS states, once again, that parents should spend more money for more safety. Of course, the median household income in 2014, per the US Census Bureau, was $51,339, which tends to be the same from year to year. Furthermore, median household debt in 2010 was $3,300, which is unlikely to have changed significantly in the last few years. Oh, and college, which most parents aspire their children attending, still costs around $23,410 if you’re aiming for average costs as an in-state student at a public 4-year school.

Last year in 2014, the IIHS reported the median amount spent by parents on vehicles for teens was $5,300. Adjusting for inflation, this yields a sum of $5,327 in 2015. The IIHS states, once again, that parents should spend more money for more safety. Of course, the median household income in 2014, per the US Census Bureau, was $51,339, which tends to be the same from year to year. Furthermore, median household debt in 2010 was $3,300, which is unlikely to have changed significantly in the last few years. Oh, and college, which most parents aspire their children attending, still costs around $23,410 if you’re aiming for average costs as an in-state student at a public 4-year school.

As a result, urging parents to spend more is unlikely to occur for a variety of reasons. So let’s look at the IIHS’ 2015 vehicle list and see how relevant it is for median parents:

They tag 81 vehicles as “best” choices and 68 as “good” choices, for a total of 149 vehicles. Of these, ideally, at least 74 should be below $5,327, with the other half above that amount, if this list is truly designed to help parents where they are, rather than where the IIHS would like them to be financially.

How many vehicles fall below the median?

Nineteen.

In other words, just under 13% of vehicles, or 19 out of 149, show up at or below the median price. An ideal list would feature 50% of vehicles in that range. Unfortunately, the list this year, much like the list last year, remains out of reach for the vast majority of American families.

2. Does the IIHS paint an accurate report of how dangerous teenage drivers are, who the most dangerous teens are, and how to reduce their danger?

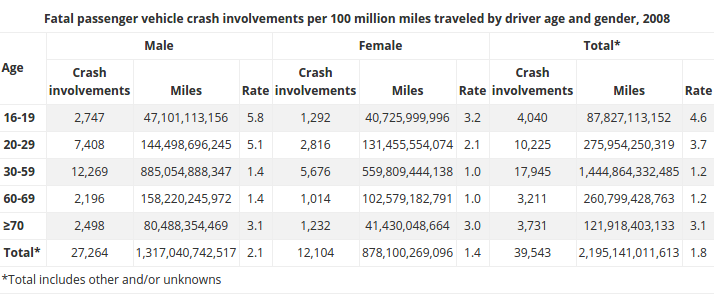

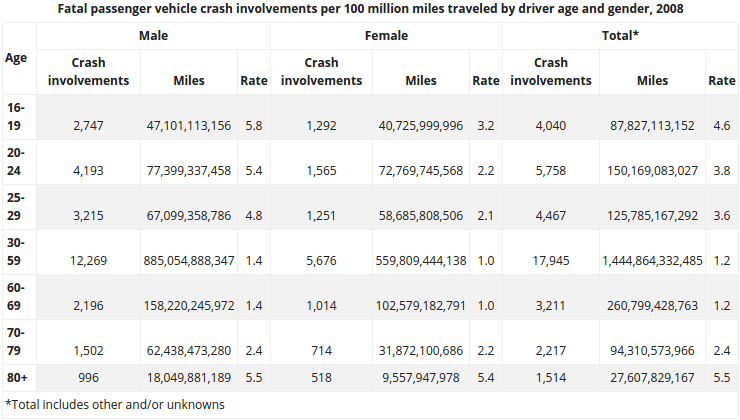

Last year in 2014, the IIHS urged parents to consider “the risks teens take” and pay more to keep them safe. However, as I noted, the groups most likely to be involved in fatal crashes are teenage males between 16 and 19, followed by young men between 20 and 29. Teenage girls are safer than *all* male drivers until male drivers turn 30. The IIHS ignored their own data when omitting this information last year. Did things change this year?

Unfortunately not. The IIHS did recommend parents choose vehicles without high horsepower, with a lot of weight, and with ESC, but said nothing about reducing the amount of unsupervised driving teenage males were allowed or delaying their acquisition of licenses. Is it a good idea to put teens in vehicles with ESC? Yes, the same way it’s a good idea to put everyone in vehicles with ESC. Is it a good idea to avoid high horsepower vehicles for teens? Yes, for the same reason it’s a good idea for adults (speed kills). Is it a good idea to suggest teens drive giant vehicles to keep them safe? I’ll tackle that in a moment.

But finally, is it helpful for the IIHS to continue to paint all teens with a broad brush when the most dangerous drivers are, quite plainly, teenage males?

No; there is much left unsaid here, and an opportunity was missed.

3. Does the IIHS continue to encourage destructive policies for all road users by encouraging parents to buy large and heavy vehicles for the least experienced drivers on the road?

Last year in 2014, the IIHS directed parents to choose bigger and heavier vehicles for their teenage drivers, and explicitly stated they wouldn’t recommend minicars or small cars to parents of teenagers. I countered that this advice only made the roads more dangerous for all drivers by encouraging a vehicular arms race through telling parents to buy large and heavy vehicles for the least experienced drivers on the road. Did this change this year?

Unfortunately not. The IIHS repeats their “every driver for him/herself” mantra by urging parents outfit their teenage drivers with vehicles capable of doing more harm to others by doing less harm to them by extension. I understand the logic behind this thought process, but it’s ultimately a futile one.

If everyone follows the advice and drives heavy vehicles, heavy vehicles offer no advantages to anyone inside them, while making the roads that much more dangerous for people who aren’t in any vehicles, such as cyclists, motorcyclists, and every single pedestrian in the country. And whether we acknowledge it or not, all of us are pedestrians at one point or another in the day, even if only when walking to and from our vehicles when leaving or arriving our homes, places of work, of food, of commerce, of worship, and so on.

Am I stating parents should only buy tiny cars for their teenage drivers? Not necessarily. But I am absolutely stating that parents should not buy large vehicles for their children, or for themselves, if not absolutely necessary.

It is the height of irresponsibility to buy vehicles that increase the already-grandiose sense of invincibility felt by far too many teenage males (which, of course, is what leads to their having a far higher rate of involvement in fatal collisions than teenage females or males of any other age before 80).

To put it frankly, the IIHS’ recommendation to avoid a number of very safe, practical, affordable, and fuel-friendly vehicles (e.g., a used Prius that yields 50 mpg while having a driver death rate better than dozens of 4000-6000 lb pickup trucks and SUVs) is an unpleasant one for a number of ethical, environmental, financial, and humanitarian reasons.

This list isn’t helpful. Let’s make one that is.

If the IIHS is unhelpful in choosing safe and budget-friendly vehicles for teenagers, which ones would you recommend in 2016, Mike, and why?

At this point, it’s clear that the IIHS’ agenda isn’t necessarily the most relevant or helpful one for parents interested in keeping their teenagers safe and financially solvent without increasing the risks they pose to others on the road (of all ages). My recommendations are based on those assumptions.

As a result, I primarily include mini (subcompact) and small (compact) cars and SUVs, add mid-sized cars, and completely leave out mid-sized and larger SUVs, minivans, and pickup trucks, which are unnecessary for most teenagers (who ideally should either be driving with parents or driving alone, and certainly shouldn’t be driving with other teens). Furthermore, all of my recommendations are around the median price parents are spending ($5,327), and all of my recommendations include vehicles with side airbags, ESC, and good frontal and good or acceptable side crash scores. All prices are based on private party costs in November 2015 in the Chicago metro area.

The safest affordable mini cars and subcompacts for teenagers in 2016

2010+ Toyota Yaris

2010+ Toyota Yaris

The Yaris is a good choice for teens on a budget who prioritize fuel economy; the EPA ratings are 29/35 city/highway in the automatic and 29/36 in the manual. From 2010 onward, ESC is standard, while side airbags are standard from 2009 onward. It has both good frontal and side crash test scores.

The safest affordable small cars and compacts for teenagers in 2016

2010+ Ford Focus

2010+ Ford Focus

The Focus sedan is another good choice for parents interested in safety, affordability, and fuel economy. It’s rated for 24/34 in the automatic and 24/35 in the manual, and comes standard with side airbags and ESC from 2010 onward, or simply with side airbags from 2008 onward. It has a good frontal score but only an acceptable side score.

The safest affordable small SUVs and crossovers for teenagers in 2016

200 5+ Honda CR-V

5+ Honda CR-V

The CR-V, along with the Yaris, is one of the two most reliable vehicles on this list, and is highly recommended for parents who would like vehicles their teens can pay to repair due to low maintenance costs. It comes with ESC and side airbags as standard features from 2005 onward. It has both good frontal and side crash test scores and is rated at 20/26 in the automatic FWD. It’s also one of only 2 vehicles on the list with an AWD option (the other is the S60).

The safest affordable mid-sized cars for teenagers in 2016

2004+ Saab 9-3

2004+ Saab 9-3

The Saab 9-3 is the most affordable vehicle on this list to buy, although probably not the cheapest to maintain. It has come with both ESC and side airbags since 2003, which is earlier than any vehicle on this list and the vast majority of vehicles ever made. It has both good frontal and side crash test scores as of 2004, and is rated at around 18/27 in the automatic.

2007+ Volvo S60

2007+ Volvo S60

Finally, the S60 is another good choice for parents interested in safety and affordability. Like the 9-3, however, it’s likely to cost more to maintain over time. It has good frontal and acceptable side crash test scores and has come with ESC since 2007 and side airbags since 2001. It is rated at around 19/28 in the best of the automatic transmissions, and is also available in AWD.

I hope you’ve found this article helpful and informative as a parent interested in finding safe and affordable transportation for you teenage child. We can’t protect them from everything, but we can certainly keep them safer without going into debt or making the roads less safe for others in our communities.

—

If you find the information on car safety, recommended car seats, and car seat reviews on this car seat blog helpful, you can shop through this Amazon link for any purchases, car seat-related or not. Canadians can shop through this link for Canadian purchases.

The chart suggests the safest drivers, both male, and female, are those between 30 and 69, or more specifically, between 30 and 59 and between 60 and 69. The 60-69 group clearly involves a number of seniors, yet they still contribute to the group of the safest drivers.

The chart suggests the safest drivers, both male, and female, are those between 30 and 69, or more specifically, between 30 and 59 and between 60 and 69. The 60-69 group clearly involves a number of seniors, yet they still contribute to the group of the safest drivers.

Last year, the IIHS published their first list of used car recommendations for teenagers, and

Last year, the IIHS published their first list of used car recommendations for teenagers, and  Last year in 2014, the IIHS reported the median amount spent by parents on vehicles for teens was $5,300. Adjusting for inflation, this yields a sum of $5,327 in 2015. The IIHS states, once again, that parents should spend more money for more safety. Of course, the median household income in 2014, per the US Census Bureau, was $

Last year in 2014, the IIHS reported the median amount spent by parents on vehicles for teens was $5,300. Adjusting for inflation, this yields a sum of $5,327 in 2015. The IIHS states, once again, that parents should spend more money for more safety. Of course, the median household income in 2014, per the US Census Bureau, was $

5+ Honda CR-V

5+ Honda CR-V 2004+ Saab 9-3

2004+ Saab 9-3

To put it another way, the average male driver is a greater risk on the road, per mile driven, than any other driver, from the moment he gets his license until the day he turns 30. That’s 14 years of being more dangerous than a senior driver of either gender, and that’s 14 years of being more dangerous than a teenage female driver.

To put it another way, the average male driver is a greater risk on the road, per mile driven, than any other driver, from the moment he gets his license until the day he turns 30. That’s 14 years of being more dangerous than a senior driver of either gender, and that’s 14 years of being more dangerous than a teenage female driver. If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can