The Swedish approach to child car seat safety is deceptively simple, yet it results in the best child traffic safety numbers on the planet. Virtually no children die from traffic incidents in Sweden each year, and this has been the case for many years now. As far as child traffic safety is concerned, they are the standard (although their western neighbor, Norway, has followed their example, and is now demonstrating stunningly low child death rates in traffic as well). I like learning from people doing things well.

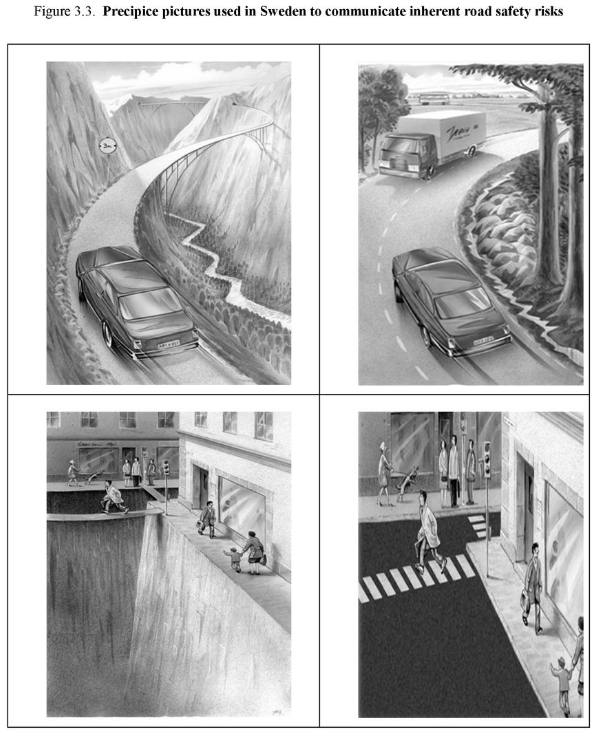

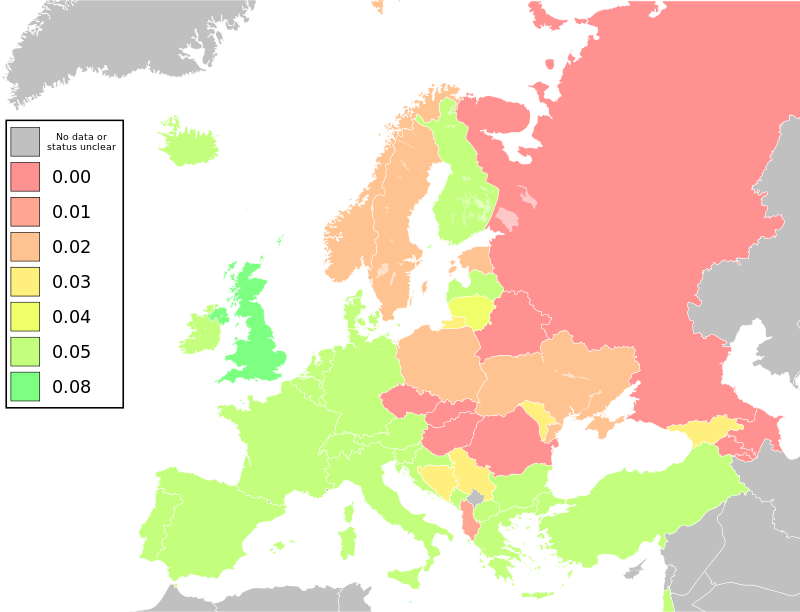

Of course, the world-class results aren’t simply due to how they restrain kids in cars–there are a number of other factors that tie in, nearly all of which are related to Vision Zero principles, a practical and philosophical belief in Sweden that no one, adult or child, should die from traffic incidents. This manifests itself in areas like nation-wide laws requiring driving with headlights on 24/7, using snow tires throughout the winter months, an acceptance of traffic cameras everywhere, extremely low alcohol limits for driving, $2000 driving licenses, and traffic speeds and road designs based on the trauma limits of the human body.

But today’s article isn’t about any of these factors, although I love writing about them. Today’s article is a quick guide to how Swedes approach car seats with their kids. Today, we’ll pretend we’re Swedish parents, and look at the kinds of seats they choose and why. The great news is that the Swedish approach is rather simple, yet quite effective, as evidenced by the near-nonexistent death rates for young children from traffic. There are only three main seats used: the infant seat, the rear-facing convertible, and the high back booster.

What kinds of car seats do Swedish parents use with infants and babies?

The first car seat nearly all Swedish children use is the infant seat (known as the cradle abroad). This is essentially the same approach as in the US; the infant seat is easy to carry and can be moved in and out of a vehicle without waking a sleeping baby (very important). Swedish parents will typically use it for the first six to nine months of life. Naturally, it’ll be rear-facing.

A great example of an equivalent infant seat in the US is the Chicco KeyFit 30. It doesn’t need to have a high height or weight limit; that doesn’t matter. What matters is that it’s easy to install and easy to carry. It’ll be used for less than a year before parents get tired of carrying it and switch to the next seat.

What comes after the infant seat, and how long do the Swedes use it?

After the infant seat, the Swedes, well-versed in the importance of extended rear-facing, invest in a rear-facing convertible seat. The typical Swedish family will rear-face until 4-5 even though there isn’t actually a law in the country requiring parents to do so. What you’ll find is a deep cultural knowledge of the value of rear-facing due to an effective and long-lasting public awareness campaign began by the government and media with guidance from research conducted throughout the country.

Parents don’t feel like outliers when rear-facing until 4-5 because everyone else is doing it; it isn’t known as “extended rear-facing” there, and parents don’t have to justify to fellow parents or spouses why they haven’t turned their car seats around. It’s just what you do.

In Sweden, you can buy car seats that allow you to rear-face all the way to 55 pounds, potentially allowing rear-facing until 6 or even longer. In the US, our best seats–The Graco Extend2Fit, Clek Fllo, Diono Rainier, Clek Foonf, and Diono Pacifica–allow you to rear-face until 50 pounds, which is a great improvement over how the car seat scene looked just a few years ago here. Fifty pounds will be enough to allow you to make it until 4 or 5, which is how long you’ll find the typical Swedish child rear-facing. The kids don’t protest it there because their parents treat it as normal, as do their grandparents and everyone else they come into contact with.

Among seats available in the United States, the Extend2Fit is one of my favorite examples for this phase, as it not only features one of the highest weight limits at 50 lbs, it also features the highest height limit (it’s 49″, or the same as the forward-facing height limit), which means you’ll might even be able to rear-face until 6 or 7 if you really want to, depending on the height of your child.

In comparison, in the US, children are only required to rear-face until 1 in all but 4 states, and 75% of children are forward-facing by their 2nd birthday. That’s too soon. Aim for at least 4 if at all possible.

What comes after rear-facing in Sweden, and for how long? And what about harnessed seats?

Once parents stop rear-facing in Sweden, they don’t typically use harnessed forward-facing seats. In fact, the general Swedish perception is that booster seats are actually safer than forward-facing seats for children of an appropriate age (i.e., 4+). The reasons for this involve research in Sweden regarding how the harness system may put more load on the neck by restraining the rest of the body (and allowing the neck to snap forward), compared to how the body moves more completely when in a seat belt, spreading forces across the body.

As a result, parents will typically move from a rear-facing convertible directly to a high-back booster. The particular booster they choose doesn’t matter too much as long as it’s a high-back booster; the reason behind this is that they keep the child in place even if she or he falls asleep in the car.

Three of the best dedicated boosters on the market today are the Clek Oobr, Peg Perego Flex 120, and Maxi-Cosi RodiFix, and I’d give the edge to the RodiFix because, like most Swedish car seats (and European ones in general), it doesn’t feature cup holders. The lack of arm rests also means your kids won’t get the seat belts stuck on them while buckling themselves in. If you’re on a smaller budget, the Britax Parkway also does a great job. Whichever seat you choose, it’s worth looking for ones that include LATCH connectors, as these will allow you to permanently attach the seats to your vehicle, preventing them from becoming projectiles when they aren’t buckled in.

Swedish parents use booster seats as long as the law requires (there is a law here regarding this), which is until they’re 135 cm tall, or 53″ tall. This is a rather common law throughout the EU.

But aren’t harnessed forward-facing seats safer than booster seats?

It’s a common belief in the US that forward-facing harnessed seats are safer than booster seats, and this is true in certain contexts. It’s true when children should still absolutely be rear-facing (i.e., under 4), simply because children who are boostered too early are at tremendous risk for suffering abdominal injuries or submarining out of their car seats.

Even beyond 4, children who don’t sit properly will be safer in harnessed seats (which force them to sit correctly) than in boosters, where they can move themselves out of safe positions. However, once children are mature enough to sit properly (i.e., straight up in the centers of their seats), there is no safety difference between harnessed forward-facing seats and booster seats. The NHTSA recommends waiting until 8 (or until children outgrow their forward-facing seats) to cover all bases here, but it’s likely that most children who are 6 or older will be able to sit appropriately enough to use booster seats.

When do Swedish parents stop using car seats and just use seat belts?

Swedish parents typically stop using car seats and switch their kids to seat belts once they’re at least 135 cm (53″) tall. See the NTF’s responses for more information here. Their recommendations are generally in line with those of the NHTSA, which recommend that children stay in booster seats until they have good belt fit, which they state is generally around when they’re between 8 and 12 years old.

Do you recommend following the Swedish approach to car seat selection?

Absolutely. The American in me wants to suggest harnessed forward-facing seats over boosters, but the evidence doesn’t support their being necessary for most children beyond 5 or 6. I do think the 5-step test for seat belt readiness is a good idea, but I also think the harness/booster debates and 5-step test aren’t nearly as important as the core element of rear-facing as long as possible. If you take nothing else from this, take that and spread the word.

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can do your shopping through this Amazon link. Canadians can shop here for Canadian purchases. Have a question or want to discuss best practices? Send me an email at carcrashdetective [at] gmail [dot] com.

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can do your shopping through this Amazon link. Canadians can shop here for Canadian purchases. Have a question or want to discuss best practices? Send me an email at carcrashdetective [at] gmail [dot] com.