This is the latest post in a series on the IRTAD report I’ve been reading, Zero Road Deaths and Serious Injuries: Leading a Paradigm Shift to a Safe System. It’s basically a field guide to how countries around the globe have made strides in developing Safe Systems / Vision Zero / Toward Zero approaches, and it’s well worth reading. I’m a fan of the Safe System approach, and have written a number of articles related to the fundamental message that all human lives matter, and none should be–or need to be–lost due to auto crashes. I’ve included a brief listing of recent articles below. If you aren’t familiar with the concept, you’ll want to check them out. If you are, skip below; there’s more information than ever about the importance of avoiding undivided roads when driving.

Isn’t safe driving just about having the newest safety materials in my car?

It’s a common misconception that auto safety is simply a question of buying the newest car possible. While that can help, the truth is that the majority of what affects our survival on the roads has to do with how and where we drive followed by what we drive. A Safe System focuses on all three factors but gives extra importance to the where, because it’s much easier to change than the human behavior, the how, yet can be much more effective, especially with a bit of help from the how and what.

Previous Safe System articles on the how and where I’ve written involve the top speeds for survivable protected and unprotected collisions, the magic of 43 mph as a survivability speed , how to ensure pedestrian safety, reasons why traffic cameras are our friends, how to double driving safety overnight, how driving less increases overall safety, reasons to drive with head lights, the safest road lanes, the benefits of snow tires, the impact of speed on kinetic energy, why it’s safer for adults to drive in Norway, why kids are safer in Norway, why Europe is safer for drivers, different standards in auto safety around the world, which are the safest and most dangerous states, and how speeding is the magic bullet.

To put it simply, this is my passion. There’s a lot we can do to increase our road safety as individuals, but the biggest changes come from changing the way our society views road safety, and the collective responsibility we have to make our roads safe for everyone. To that end, my most recent article on the topic involves ending the blame game and assuming a more humanistic, cooperative, and ultimately effective approach toward safer roads.

OK, I’m up to speed. What does the report say about driving safety in relation to undivided roads?

On page 92, the report notes:

Divided roads were the most effective factor in avoiding fatalities among vehicle occupants.

Slightly later, on page 92, we read:

An example of a “primary” Safe System treatment [is] a median barrier, as this will virtually eliminate (in over 90% of cases) fatal head-on crashes, while a “supportive” treatment would be a wide centreline with rumble strips that will make them less likely. It is strongly recommended that the primary treatments are employed where possible.”

This is significant. We have research suggesting the single most effective way of avoiding vehicle fatalities are to use divided roads, or to not use

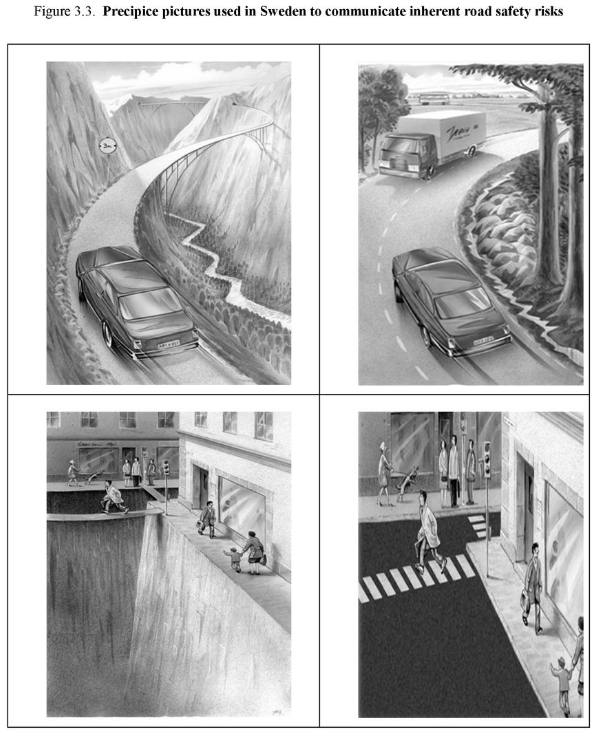

undivided roads. What is a divided road? That’s answered within the second quotation; it’s a road system with a median barrier that divides two opposing lanes of traffic. To put it another, more visual way, it’s a road that looks like the one on the left. Divided roads aren’t nearly as visually appealing as undivided ones, but they’re much, much safer. This is also why interstates are traditionally the safest kinds of roads we can drive on per mile, despite featuring the highest speeds–it’s because they’re inherently designed to avoid vehicles crashing into each other at high rates of speed.

What can we do? Do we simply avoid all undivided roads?

In a word, yes! Whenever possible, drive on divided roads. However, it’s not always that simple. Let’s answer the “what can we do?” question with a bit more detail.

If we know divided roads are the most significant factor in reducing vehicle fatalities, what do we do with this information? Well, we can certainly call or write letters to our local, state, and federal departments of transportation. We can advocate for change and point to reports like the IRTAD report above. However, while waiting and advocating for change on larger levels, we can take action on an individual level. This is where change begins. We lower that 35,000 annual fatality figure one saved life at a time.

We can drive on the kinds of roads we know from research are safest, and avoid undivided roadways whenever possible. I’ve written about this before, and I’ll continue to do so as long as I read or write about stories involving fatalities on undivided roads. These are the quintessential “drifting across the midline” crashes; they’re the ones where one vehicle inadvertently enters the opposing lane of traffic and isn’t stopped until it crashes directly into another vehicle. They are violent and bloody and unnecessary. They can be all but eliminated simply by installing barriers between the lanes. Until that day comes, and these kinds of roads are eliminated or speed limited (remember that Safe System practices dictates a 43 mph limit for undivided roads), your best bet is to avoid them as much as you possibly can. You literally cut your odds of being involved in a fatal head-on crash (which, by the way, is the most frequent fatal multi-vehicle collision) by 90%–almost completely–by avoiding these kinds of roads.

Don’t wait for your state department of transportation to catch up to best practices. Start living them, and spread the word.

—

If you find the information on car safety, recommended car seats, and car seat reviews on this car seat blog helpful, you can shop through this Amazon link for any purchases, car seat-related or not. Canadians can shop through this link for Canadian purchases.

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can

The

The