Sweden is essentially the blueprint when it comes to best practices for car seat safety, but there are also a number of things we can learn from the country when it comes to general car safety. This will be the start of a series of posts investigating the safety of Swedish roads and determining what we can learn from them at a national, state, community, and individual level to make our roads safer for everyone.

This article from the Economist provides a brief primer to recent developments in Swedish road safety. A record low was set in 2013, with only 264 people dying in car crashes. The current death rate (for 2013) is approximately 3 per 100,000 Swedes, compared to 11.4 per 100,000 in the US, and 40 per 100,000 in the Dominican Republic, where the roads are the most dangerous on the planet in per capita terms.

To provide another perspective, in 2012 in the US, the most recent year for which full data is available, 33,561 people lost their lives, while the population was 313.9 million, for a rate of 10.7 per 100,000. There are around 9.7 million Swedes. If the US 2012 death rate could have been reduced to Swedish 2013 levels, only 9,417 individuals would have perished, instead of 33,561.

That’s an incredible difference, isn’t it?

The last time the US had an auto death rate as low as 3 per 100,000 was in 1912, the year the Titanic sank. Back then, 2,968 people died, and the US population as 95 million. The last time we lost only 9,000 individuals to car crashes was in 1917, when we lost 9,630, and there were 103 million in the country. By then, though, the death rate was almost was bad as it is now, as it had already soared in just five years to 9.3 per 100,000.

So what has made the difference?

Deaths from car crashes are unacceptable to the Swedish government

Well, a big part of it was the “Vision Zero” project.

In 1997 the Swedish parliament wrote into law a “Vision Zero” plan, promising to eliminate road fatalities and injuries altogether. “We simply do not accept any deaths or injuries on our roads,” says Hans Berg of the national transport agency. Swedes believe—and are now proving—that they can have mobility and safety at the same time.

Interesting, isn’t it? The goal of completely eliminating fatalities and injuries in collisions, and the perspective that any deaths or injuries were unacceptable. It’s an idea that would be greeted with scorn in the US, as here we accept car crashes and the needless miseries they bring as facts of life, despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of them are preventable.

Planning has played the biggest part in reducing accidents. Roads in Sweden are built with safety prioritised over speed or convenience. Low urban speed-limits, pedestrian zones and barriers that separate cars from bikes and oncoming traffic have helped.

Planning has been mentioned by a number of sources as one of the factors that sets the US apart (in a bad way) from fellow rich countries making much bigger gains in reducing deaths. Look at that–roads built for safety over convenience. That means roads that slow travelers, since speed = death, as you’ve likely seen from so many calculations on this blog. It shouldn’t be convenient to travel at 70 or 80 mph by car; people, by far and large, aren’t capable of managing vehicles with the necessary accuracy at those speeds.

Pedestrian deaths increase disproportionally with speed

Similarly, lower speed limits in urban zones are essential. A car hitting you at 20 mph has somewhere around a 5% chance of killing you. By 30 mph, those odds jump to 50%, and by 40 mph, you’ve got a 95% chance of being dead. It’s not linear; it’s exponential. This is why car crashes become serious so quickly with even just a bit of speeding. Yet speeding runs rampant throughout the US, and we pay for it with blood.

How do we protect cyclists – and how do cyclists protect us?

The same issue arises when discussing traffic separation. Bicycles are not cars; they have no inherent protection, much like pedestrians, and must be separated from vehicular traffic, much like pedestrians. In bike-friendly countries, bicycles have dedicated lanes, like sidewalks, but for bicycles, that go everywhere roads do. As a result, people feel safe to ride, which makes the roads even safer, as drivers learn to look out for cyclists. It’s a virtuous cycle.

Building 1,500 kilometres (900 miles) of “2+1” roads—where each lane of traffic takes turns to use a middle lane for overtaking—is reckoned to have saved around 145 lives over the first decade of Vision Zero. And 12,600 safer crossings, including pedestrian bridges and zebra-stripes flanked by flashing lights and protected with speed-bumps, are estimated to have halved the number of pedestrian deaths over the past five years.

This is an elaboration of previous points. The most vulnerable travelers (pedestrians and cyclists) need to be protected. 2+1 roads, furthermore, in Sweden, are frequently designed with cable barriers, which are a great way of preventing the head on collisions that take so many lives on rural roads in the US (which are where most road fatalities in the US occur). The Swedes realized that it simply didn’t make sense to have human-steered vehicles hurtling toward each other in opposite directions at breakneck speeds with nothing between them but air and a broken yellow line.

This is an elaboration of previous points. The most vulnerable travelers (pedestrians and cyclists) need to be protected. 2+1 roads, furthermore, in Sweden, are frequently designed with cable barriers, which are a great way of preventing the head on collisions that take so many lives on rural roads in the US (which are where most road fatalities in the US occur). The Swedes realized that it simply didn’t make sense to have human-steered vehicles hurtling toward each other in opposite directions at breakneck speeds with nothing between them but air and a broken yellow line.

Strict policing has also helped: now less than 0.25% of drivers tested are over the alcohol limit. Road deaths of children under seven have plummeted—in 2012 only one was killed, compared with 58 in 1970.

Sobriety testing and checkpoints are considered “meddling” by “big government” in the US, but in other countries where citizens place higher weight on the collective good, these checkpoints are much more common, and the separation of alcohol and the automobile is taken far, far more seriously.

And because this is also a car seat blog, here’s another reference to that amazing commitment to child safety. Only one child under 7 died in a car collision in 2012. A direct comparison is hard to find in the US, but in 2012, 480 children 8 and under died while passengers. At the Swedish proportion (1/264), we would have expected around 127 children 8 and under to have died. The fact that nearly 4x as many died is as clear an indicator as any that the Swedes are protecting their children in cars much better than we are. I strongly suspect a default acceptance of ERF plays a significant role in this magnitude of a difference.

Eventually, cars may do away with drivers altogether. This may not be as far off as it sounds: Volvo, a car manufacturer, will run a pilot programme of driverless cars in Gothenburg in 2017, in partnership with the transport ministry. Without erratic drivers, cars may finally become the safest form of transport.

The article ends with a look toward the future and a nod toward driverless cars. While I doubt driverless cars will surpass air travel in safety per mile, I do fully believe they will overwhelmingly surpass human-driven cars in safety, and cannot wait until their presence is as prevalent as the seat belt.

Oh, and the Volvo project has already started.

Oh, and the Volvo project has already started.

So what is there to learn from this? Clearly, the Swedes are taking a different approach to auto safety than we are here in the United States. People-centered (rather than auto-centered) planning, lower speed limits, much tighter restrictions on alcohol, and a commitment to eliminating deaths, or an entirely different conceptualization of the inevitability of the auto fatality, are all reaping benefits.

When can we try this here?

—

If you find the information on car safety, recommended car seats, and car seat reviews on this car seat blog helpful, you can shop through this Amazon link for any purchases, car seat-related or not. Canadians can shop through this link for Canadian purchases.

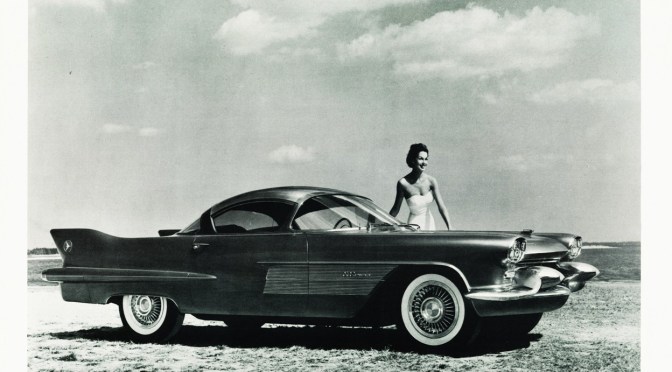

Something I’ve learned over the last several years of looking into crashes is that there are a number of persistent myths floating around the real and online world related to car safety, and one of the most persistent ones is that old cars–and I mean really old, like vintage old cars–were safer than new ones. According to the myth, old cars had steel and things like that, while new cars have airbags and crumple and just aren’t as safe. In fact, some people go as far as to say that the reason new cars have airbags, crumple zones, and plastic parts is because they aren’t as safe.

Something I’ve learned over the last several years of looking into crashes is that there are a number of persistent myths floating around the real and online world related to car safety, and one of the most persistent ones is that old cars–and I mean really old, like vintage old cars–were safer than new ones. According to the myth, old cars had steel and things like that, while new cars have airbags and crumple and just aren’t as safe. In fact, some people go as far as to say that the reason new cars have airbags, crumple zones, and plastic parts is because they aren’t as safe.