Higher speed limits, like an entire bag of Hershey’s Kisses, are one of those things that sound good but really aren’t good for you. Politicians love them because they know people won’t oppose them. After all, who would object to being able to speed a bit more on the highway? It’s something we all do anyway, right?

Higher speed limits, like an entire bag of Hershey’s Kisses, are one of those things that sound good but really aren’t good for you. Politicians love them because they know people won’t oppose them. After all, who would object to being able to speed a bit more on the highway? It’s something we all do anyway, right?

The problem is that speeding is already a factor in 1 out of every 3 auto fatalities in the United States, which means that if you speed, or if someone else does, your life and the lives of your loved ones automatically become less safe. So why do we keep letting our elected leaders lead us into bad decisions?

Let’s take a look at speed limits throughout the US, what we know about how speed affects crash forces, and then tie this into what we can do to increase the safety of those we love on the road.

How are daytime speed limits distributed throughout the United States?

Speed limits throughout the US range from 60 mph in one state, Hawaii, to 85 mph in sections of Texas. Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming, and South Dakota are nearly as bad with PSLs (posted speed limits) at 80. The remaining states are mostly at 75 or 70 mph, with several New England states (New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont) and Alaska at 65 mph.

How have speed limits changed over time in the US?

Speed limits have increased nearly uniformly throughout the states since 1995, when the National Highway System Designation Act repealed a 55 mph speed limit set by Congress in 1973. Prior to then, most states had had speed limits between 65 and 70 mph, and since then, particularly in recent years, many states have begun pushing ever higher speed limits, with potentially deadly consequences.

How do higher speeds increase the likelihoods of a crash?

Higher speeds make crashes more likely because there are finite limits on both human reaction times and vehicular braking times and distances. Research suggests human reaction times vary from moment to moment and situation to situation, but even using a conservative estimate of 2 seconds, a car stopping distance calculator and measurement comparer provides discomforting numbers:

At 20 mph, a speed at which 5% of pedestrians are likely to be killed when struck by a vehicle, 2 seconds of reaction time lead to 59 feet of “thinking” distance, or the time needed to see a hazard, decide to brake, and press the brakes. Beyond that, you also need 20 feet of braking distance, resulting in 79 feet of total stopping distance. That’s already more than the length of a semi-trailer and cab, or nine-tenths as long as the distance between bases in baseball.

How about at 40 mph? That’s a speed at which around 95% of pedestrians are likely to be killed when struck by a vehicle. It’s also a speed which the IIHS considers a severe crash when involving head-on collisions, and it’s the speed at which they conduct their moderate and small frontal overlap crash tests.

At 40 mph, 2 seconds of reaction time lead to 117 feet of “thinking” distance. Add 80 feet of braking distance, and you get 197 feet of total stopping distance, or nine-tenths the wingspan of a 747, or half the length of an NFL football field.

At 60 mph, which is slower than the highway PSLs in most states in the US (never mind the speeds people are actually reaching), it takes 176 feet just to *process* something enough to hit the brakes in 2 seconds. That’s already about the entire distance it takes to see, react, and stop before a hazard at 40 mph. However, things aren’t done there; you also need 180 feet of braking distance, which doubles your stopping distance and brings you to 356 feet.

That’s the length of a football field (NFL or soccer).

I don’t know if you’ve ever looked out at a football field and imagined not being able to avoid hitting a car parked at the end of it, but that’s a huge distance to deal with in an emergency situation.

At 80 mph, a speed legally permissible, at least in part, in 7 states, and a speed which many drivers in another 20 or so states regularly reach due to 70-75 mph limits, there’s practically no hope of avoiding an emergency. With 2 seconds of thinking time, you need 235 feet just to begin with, or a full 2/3rds of that NFL field / soccer pitch we just visualized, and another 320 feet to brake, bringing you to 554 feet, or around 1.5 football fields.

Why do higher speeds make collisions more likely to be fatal?

Higher speeds make collisions much more likely to be fatal because energy increases with the square of velocity. This is a fancy way of saying that increasing the speed of an object affects the force of a collision much more than increasing how much it weighs. It’s why being hit by a bullet shot out of a gun hurts a lot more (sometimes fatally more) than being hit by a bullet thrown at you.

Here’s a quick example with numbers thanks to a kinetic energy calculator:

At 20 mph, a prototypical mid-sized 3,200 lb car (e.g., a Toyota Camry) has 58,014 J of energy, or 58 KJ. At 40 mph, if energy increased linearly, we’d expect the Camry to carry 116 KJ of energy, or 200% as much as it did at 20 mph (due to 40 being 2 x 20).

However, it doesn’t.

Instead, it has 232 KJ, or 400% of (4x) the energy it carried when traveling at 20 mph. The speed was doubled, but the forces were quadrupled.

This is what it means for energy to increase with the square of the velocity. The energy in a collision increases much more quickly with speed than it does with weight. Or to put it simply, although the speed was merely doubled, the forces were quadrupled.

Our hypothetical Camry will be tested by the IIHS in what simulates a 40 mph collision with another Camry, resulting in a transfer of energy of 232 KJ. A Camry receiving a “good” frontal score is one that dissipated that energy without transferring so much of it into the driver that the driver dies. This, as I wrote before, is already considered to be a severe collision.

So what happens at highway speeds?

Well, at 60 mph, the Camry suddenly has 522 KJ of energy, or 900% of the energy it carried when traveling at 20 mph (rather than 300%, which you’d expect from 60 being 3 x 20). It has 225% of the energy it carried when traveling at 40 mph (rather than 150%, which you’d expect from 60 being 1.5 x 40).

To put it another way, the Camry needs to dissipate 9x as much energy at 60 mph as it did at 20 mph, or 2.25x as much energy at 60 mph as it did at 40 mph. Many people can’t handle receiving 225% as much energy as their vehicles are designed to protect them from, which is why there are many fatalities from head on collisions at 60 mph. Many of these fatalities would have been survivable at 40 mph.

At 80 mph, death is nearly certain. The Camry has a whopping 928 KJ of energy, or 400% (4x) as much energy as it did at 40 mph, even though it’s “only” going twice as quickly. It has 178% of the energy it did when traveling at 60 mph, or nearly 2x as much, even though it’s “only” 20 mph faster.

Remember–crash tests are conducted at 40 mph for head on collisions, and there are a great many fatalities at 60 mph. At 80 mph, you or your loved ones have virtually no chance of survival in a crash, because the human body is not designed to sustain 400% of the forces at which cars are designed to make survivable (those at 40 mph collisions). The math doesn’t work.

How do we make people follow speed limits?

This is an excellent question. Basically, we have to enforce them, whether through police patrols or speed cameras. As long as it’s permissible from state to state to exceed speed limits by 5, 10, or even 20 mph, we’ll continue to see needless tragedies. As long as speeding is socially acceptable, people will speed in the belief that they are uncatchable, invincible, and perfectly in control of their safety and their vehicles.

They aren’t. Driving the speed limit–or below it–is one of the most effective steps you can take to increase your safety and the safety of your loved ones every single time you drive.

—

If you find the information on car safety, recommended car seats, and car seat reviews on this car seat blog helpful, you can shop through this Amazon link for any purchases, car seat-related or not. Canadians can shop through this link for Canadian purchases.

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can

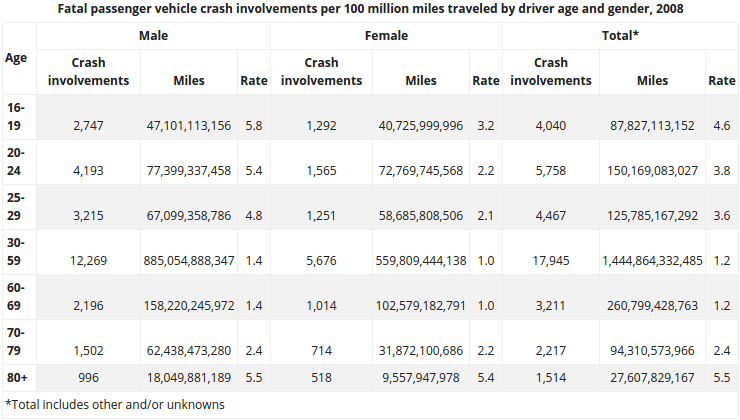

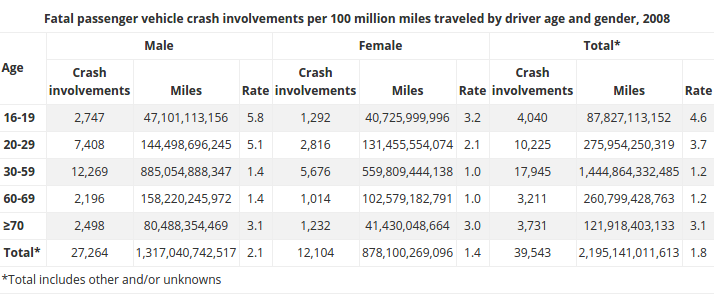

The chart suggests the safest drivers, both male, and female, are those between 30 and 69, or more specifically, between 30 and 59 and between 60 and 69. The 60-69 group clearly involves a number of seniors, yet they still contribute to the group of the safest drivers.

The chart suggests the safest drivers, both male, and female, are those between 30 and 69, or more specifically, between 30 and 59 and between 60 and 69. The 60-69 group clearly involves a number of seniors, yet they still contribute to the group of the safest drivers.