This is the second installation in a 3-part series unpacking and refuting US myths on Swedish road, car, and car seat safety. Last month, we looked at how extended-rear facing in Sweden, unlike in the US, was a mainstream idea long before 2011. We also talked about how a relinquishment of parental authority led to toddlers in the US (unlike in Sweden) telling their parents when they were done rear-facing, and how, most importantly, the reality-based community, whether in Sweden, the US, or elsewhere, was not debating the benefits of rear-facing. With all of that under our belts, let’s dig a bit deeper through the article in question. For additional context, of course, you can read a range of articles I’ve already written on the topic, such as when comparing European roads to US roads, calculating the differences between Swedish and US annual mileages, describing Volvo’s Vision Zero plans, advocating rear-facing past 2 as in Sweden, reviewing Swedish car seat safety vs US ones, sharing why you can’t buy Swedish car seats in the US, explaining Swedish car seat policies, contrasting Swedish booster practices to ours, or when deconstructing Swedish rear-facing myths.

Swedish car seats aren’t that much different from those used in the US

How do Swedish parents manage this? For one thing, rear-facing car seats in Sweden and other parts of Europe are different from those here. They are often built with a bar that comes down from the car seat to rest on the floor of the car. This allows the seat to rest farther from the back of the car’s rear seat, giving the child much more room. Parents in Sweden find it easier to get bigger children into them. Such seats, which are not available in the United States, were also found to be safer in the sled tests than the versions we use.

This information is partially right, but it’s also partially wrong. As I’ve noted elsewhere, it’s true that Swedish car seats typically have foot props (which are designed to reduce downward rotation after frontal collisions) while US seats almost never do. However, not all Swedish seats use them, but they still pass the same safety standards.

Similarly, in the US, some car seats (e.g., the Clek Fllo) do come with anti-rebound bars, which serve the same function as rear-facing tethers found in many Swedish car seats. Rear-facing tethers to allow for rear-facing tethering, which, while available in the US for select seats, is also a very rare feature. However, as with foot props, there are many Swedish seats that don’t use rear tethers yet ass the same safety tests. The key point here is that while these are beneficial features, you can make a safe car seat without either of them.

The additional assertions by the author above about Swedish seats offering more room aren’t necessarily backed up by facts; the Britax Two-Way is 72 cm tall (28.3 inches), 50 cm deep (19.7 inches), and 47 cm wide (18.5 inches). In comparison, the Clek Fllo is 26-31 inches tall depending on the height of the headrest, is 24 inches deep, and 17 inches wide. To put it simply, while some Swedish seats use less space than their American counterparts, others use more. And the seats themselves aren’t necessarily safer. The differences in child death rates across both countries can primarily be explained by differences in how the seats are used, how their parents are driving, and how the infrastructure and culture are set up to encourage safer and less risk-taking behaviors.

The infrastructure makes a much larger difference in whether you make it home

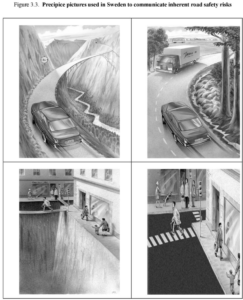

Because accidents are inevitable, Swedish regulations aim to make them nonlethal. Roads rely more on roundabouts, less on intersections. Cars are not allowed to turn at all when pedestrians are crossing. There are national camera enforcement policies. Sweden also focuses on pedestrian bridges, and separates cars from bicycles and oncoming traffic.

Now we’re getting on the right track. The Swedish government has taken great pains over the years to make their road network reflect the realities of its users. Through Vision Zero, they’ve implemented a range of best practices regarding the best ways to reduce the risks of human-vehicle interactions. As noted in the passage above, roundabouts, despite Americans’ mistrust of them in the United States, have long been recognized as far safer methods of dealing with intersections than our standard 90-degree t-bone factory approach in the United States. The intuitive reason behind roundabout safety is because they’re impossible to ignore and speed through, unlike 4-way or 2-way stops, where deadly results can occur from one vehicle refusing to cede the right of way to another.

I’ve written about intersection collisions before, such as in the case of a pregnant schoolteacher who drove through a 55 mph-grade intersection on a country road without having the right of way, simply because the sign had been knocked down in an overnight thunderstorm. She was killed by a vehicle that hit her on the driver’s side while crossing the intersection. Of course, if she’d entered the intersection only a second or two earlier or later, she’d likely have killed the occupants of the vehicle that killed her–or missed them entirely. This “roll the dice” approach to life and death we’re so willing to accept in the United States results in the needless deaths of tens of thousands of people every single year from auto traffic. A roundabout, in contrast, forces drivers to merge (much as how our highway systems don’t ask drivers entering or leaving the highway to make 90 degree turns in front of oncoming traffic to do so), dramatically reducing the odds of 90-degree collisions, which are more likely to be fatal than front-or rear collisions.

Protecting the vulnerable road users protects us all

Similarly, the Swedish restriction on turning into crosswalks isn’t because the Swedes don’t value their time; it’s because numerous studies have attested to the greater danger posed to pedestrians by rules allowing vehicles to enter crosswalks instead of by unilaterally giving pedestrians the right of way when traffic signals indicate as much. If you think about it, allowing vehicles to enter pedestrian right-of-way crosswalks when drivers deem it safe makes about as much sense as allowing drivers to run red lights when they’re sure oncoming traffic is far enough away. The reward is a small gain in efficiency; the risk is a large leap in fatalities.

Finally, both the much greater presence and societal acceptance of traffic cameras in Sweden compared to the US and the far greater attention given to creating separate infrastructure (i.e., sidewalks and cycle paths) for pedestrians and cyclists go a long away toward reducing risk-taking behaviors in drivers and increasing safe options for navigation when walking and cycling. As I’ve noted numerous times elsewhere, pedestrians and cyclists have no crash protection whatsoever from a multi-ton vehicle; the only safe solution is to keep vulnerable road users separate from protected ones, which means separate infrastructure.

We’ll end this dissection with part 3, where we’ll examine the additional changes Swedes have collectively made to driving behaviors and road infrastructure to bring ever-higher levels of road safety to children and adults alike.

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can buy my books here or do your shopping through this Amazon link. Canadians can shop here for Canadian purchases. Have a question or want to discuss best practices? Send me an email at carcrashdetective [at] gmail [dot] com.

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can buy my books here or do your shopping through this Amazon link. Canadians can shop here for Canadian purchases. Have a question or want to discuss best practices? Send me an email at carcrashdetective [at] gmail [dot] com.

The Impreza hatchback (not sedan) also had an estimated driver death rate of 12 during the 2012-14 model year, with 8 of those deaths again predicted to occur in multi-vehicle crashes. The exposure was based on 245,970 registered vehicle years, a figure roughly 1/5th the size of the Outback’s, resulting in a much larger confidence bound (it spanned 34 instead of 16 as with the Outback). As with the Outback’s driver death rate, we need to remember that the number doesn’t mean 12 drivers died while driving Imprezas; it means that if we looked at 500,000 drivers behind the wheel of 500,000 2012-14 Impreza hatchbacks over 2 years (or 1 million over 1 year), we’d expect 12 to die over that time period.

The Impreza hatchback (not sedan) also had an estimated driver death rate of 12 during the 2012-14 model year, with 8 of those deaths again predicted to occur in multi-vehicle crashes. The exposure was based on 245,970 registered vehicle years, a figure roughly 1/5th the size of the Outback’s, resulting in a much larger confidence bound (it spanned 34 instead of 16 as with the Outback). As with the Outback’s driver death rate, we need to remember that the number doesn’t mean 12 drivers died while driving Imprezas; it means that if we looked at 500,000 drivers behind the wheel of 500,000 2012-14 Impreza hatchbacks over 2 years (or 1 million over 1 year), we’d expect 12 to die over that time period. Finally, let’s look at the XV Crosstrek. It had the greatest estimated rate of driver deaths at 17 for the 2013-14 model years, with 6 predicted multiple vehicle fatalities. The exposure was based on 173,380 registered vehicle years, the smallest of the three wagons. As a result, it had the largest confidence bound at 48 instead of 34 as with the Impreza hatchback or 16 as with the Outback. As a reminder, the IIHS won’t include any vehicle in their calculations with fewer than 100,000 registered vehicle years, and a registered vehicle year is one vehicle registered for a full year. Below 100,000, the IIHS either feels the model shows too much error or too large of a confidence bound for them to be taken seriously. At any rate, the driver death figure again suggests that if 1 million drivers drove 1 million 2013-14 Crosstreks for a year throughout the US, we’d expect 17 of them to die.

Finally, let’s look at the XV Crosstrek. It had the greatest estimated rate of driver deaths at 17 for the 2013-14 model years, with 6 predicted multiple vehicle fatalities. The exposure was based on 173,380 registered vehicle years, the smallest of the three wagons. As a result, it had the largest confidence bound at 48 instead of 34 as with the Impreza hatchback or 16 as with the Outback. As a reminder, the IIHS won’t include any vehicle in their calculations with fewer than 100,000 registered vehicle years, and a registered vehicle year is one vehicle registered for a full year. Below 100,000, the IIHS either feels the model shows too much error or too large of a confidence bound for them to be taken seriously. At any rate, the driver death figure again suggests that if 1 million drivers drove 1 million 2013-14 Crosstreks for a year throughout the US, we’d expect 17 of them to die.