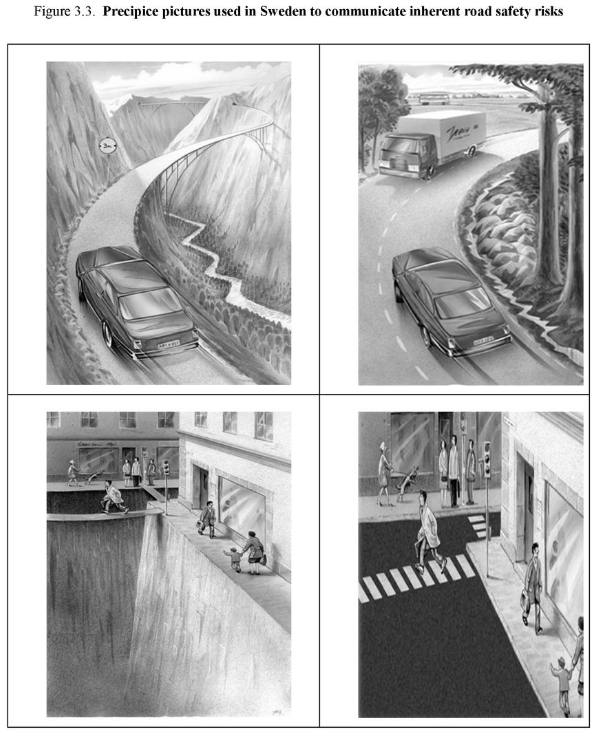

A few months ago, while perusing my favorite international safety organization, the International Traffic Safety Data and Analysis Group (IRTAD), I came across a recent report titled Zero Road Deaths and Serious Injuries: Leading a Paradigm Shift to a Safe System. It’s 172 pages of Vision Zero talk, which made for excellent evening reading. Within the report and within a section on the efforts various countries had made to raise awareness of the dangers of auto traffic, I came across this series of graphics (on page 46) published by one of the pioneers of Vision Zero, Sweden.

Specifically, the Swedish Transportation Agency, the Swedish equivalent of the NHTSA, sought to show the public in a naturally understandable way how the risks we exposed ourselves to while driving were significant ones, based on the premise that people were inherently more likely to understand the risks of high levels of kinetic energy when applied vertically compared to when applied horizontally.

To put it simply, people naturally understand how dangerous it is to fall from great heights than we get how dangerous it is to crash into obstacles at high speeds. There are likely strong evolutionary reasons related to this that have to do with falling from trees and off cliffs, but whatever the reason, this way of connecting with people seems to have some effect in raising risk awareness.

Survival speeds and Shared Responsibilities

As a reminder, Vision Zero principles are based on the ideas that road systems should be designed in ways that eliminate the risk of death or serious injury from auto use. In contrast to the predominant way of approaching road safety in the US and in most low- and middle-income countries, the risks and responsibilities of road use are not primarily assumed to rest with the end user (e.g., the passenger vehicle occupant, the cyclist, the pedestrian, the child), but are designed to be shared equally across road users, road designers, policy makers, and vehicle manufacturers.

As a result, in the examples above, it’s not simply the responsibility of the car driver to avoid being hit by the truck while navigating the turn, or the pedestrian to avoid being hit by a motor vehicle while crossing the street. In the car/truck example, both drivers should certainly be paying attention, but the truck should be designed in a way that minimizes the risk of injury it poses to others relative to its size, while the car should also be designed to offer as much protection as reasonably possible (e.g., being equipped with a crashworthy structure, seat belts, airbags, etc). Additionally, the roadway, being one that presents a risk of head-on vehicle-vehicle collisions, should have a posted and enforced speed limit no greater than 70 kph, or 43 mph, not 45 or 50 or 55 or even 65 mph as is the case in many rural areas throughout the United States.

In the second example, the zebra crossing should be clearly marked and clearly visible to give pedestrians a clear view of traffic and traffic a clear view of pedestrians. The pedestrian should have the right of way, always, and that right of way should always be defended and enforced. The traffic on that road should not be traveling at any higher than 30 kph, or 18 mph, since it has the potential to come into contact with pedestrians, and the survival rate when hit at under 20 mph is at around 95%. The roadway should be narrow enough to naturally encourage motorized traffic to travel more slowly and cautiously, as well as to make it possible for pedestrians to traverse it without spending exorbitant amounts of time in a highly vulnerable position.

Best practices aren’t secret practices; they’re just ignored ones in the United States

These are just a handful of safety modifications that should be present in two situations highlighted above. How many of them do you find present when you find yourself in either of the above scenarios? Because each factor, when present, reduces the risk of injury or death if and when a collision occurs while also reducing the risks of collisions occurring to begin with. Conversely, each factor, when absent, increases the risk of collision while simultaneously increasing injury and fatality risks should said collisions occur.

Best practice in auto safety isn’t a mystery; we know what should be done. The trick is to convince the people with the power to put best practices into place that it’s worth more to make these changes than it is to accept things the way they are.

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can do your shopping through this Amazon link. Canadians can shop here for Canadian purchases. Have a question or want to discuss best practices? Join us in the forums!

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can do your shopping through this Amazon link. Canadians can shop here for Canadian purchases. Have a question or want to discuss best practices? Join us in the forums!

The

The

Who

Who

2017 Volvo V90

2017 Volvo V90