One of the points I try to drive home on this blog is that there are really only two ways to make driving safer for yourself and your loved ones: the first is to drive safer vehicles, and the second is to drive with safer techniques. I recently focused on some of those safer techniques here, and estimated that following them 100% of the time could cut your risk of being involved in a fatal crash by half, based on the fact that roughly 50% of auto fatalities don’t involve crashes with other vehicles, but traumas like rollovers, hitting embankments or trees, or simply leaving the roadway.

However, there is an even more basic way to make driving twice as safe, reducing your risk of being involved in a fatal crash by 50%. And unlike the previous set of tips, which were mainly focused on driving more defensively to reduce your risks of a single vehicle crash, this tip reduces both your risks of single- and multi-vehicle crash involvement. What is it?

You’re half as likely to be involved in a fatal crash if you can reduce your annual mileage by 50%.

This might sound like a tip so obvious that it doesn’t merit mention, but with the stakes as high as they are (driving is literally a matter of life and death for the approximately 90 people who die every single day of the year on our roads in the US), it’s worth considering and trying to implement. To put it simply, the less you drive, the less likely you are to be involved in fatal crashes with other vehicles or with your vehicle in isolation. This holds true no matter how safe of a vehicle you’re already driving. It holds true no matter how good (i.e., safe) of a driver you already are. It holds true no matter how many miles you already are (or aren’t) driving. It holds true no matter which state or country you’re driving in. It’s pretty fool proof.

If only it were that easy! I have to drive for work / family / daily life reasons!

I’m not saying we should all go and sell our cars now, or at least park them and throw away the keys. I understand the realities of life; we have jobs and families and daily chores and expectations to meet. The kids have school and soccer practice and band and all kinds of things (although hopefully not too many things). Life is busy. But at the same time, every mile counts, and they can either count for us or against us. It’s worth taking a look at what “normal” mileage is in the US, and comparing it to your personal figures to see if you can’t reduce it a little.

How many miles does the average American drive, and does it vary by age or gender?

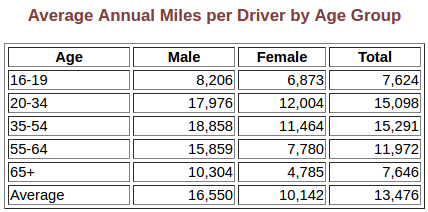

These are great questions. Per the Federal Highway Administration, which tracks annual mileage across age and gender lines, male drivers drive more than female drivers at every stage of life, while the most mileage-heavy stages of life for men and women respectively are at 35-54 (18.858 miles) and 20-34 (12,004 miles). Overall, men average approximately 16,500 annual miles while women average approximately 10,142 miles. The national average across all ages and genders is around 13,500 miles per year. What does this mean for you?

These are great questions. Per the Federal Highway Administration, which tracks annual mileage across age and gender lines, male drivers drive more than female drivers at every stage of life, while the most mileage-heavy stages of life for men and women respectively are at 35-54 (18.858 miles) and 20-34 (12,004 miles). Overall, men average approximately 16,500 annual miles while women average approximately 10,142 miles. The national average across all ages and genders is around 13,500 miles per year. What does this mean for you?

Well, perhaps you’re between 20 and 54, as are the majority of (though certainly not all) readers of this blog. If you’re a man in this age range, you’re probably driving between 18,000 and 19,000 miles per year. That’s an astonishing 51 miles a day. If you can cut your miles in half, you’ve just cut your risk of dying in a car crash in half. If you’re a woman in this age range, you’re probably driving between 11,500 and 12,000 miles a year, or just over 32 miles a day. This is far better than what most men in these age ranges are driving, but if you can cut this in half, again, you’ve just reduced your risk of death by 50% without buying a safer vehicle or changing anything about the way you drive (although I heartily recommend making such changes too!).

Are annual miles why women are less likely to be involved in fatal crashes than men across all stages of life?

I’ve written before about how women are safer drivers than men at all stages of life. On the surface, when combining that information with the chart above, it might be easy to presume that women die less in crashes simply because they drive less. While that is true in absolute numbers, the truth is that women also have a lower rate of involvement in fatal crashes per mile traveled. In other words, if a man and a woman drive 10,000 miles per year, the woman will still be less likely to be involved in a fatal crash. This is because female drivers are more likely to make use of the safe driving techniques I’ve written about earlier, or at least less likely to make use of unsafe driving techniques. It all adds up, for better or for worse.

If you can combine the ethos of driving safely with that of driving as little as possible, you eventually get to a point where your odds of dying in a car crash drop to effectively zero. On the way there, you’ll be much safer than almost every other driver on the road, and that much more likely to keep your family safe and make it back to your loved ones every day. These are things worth striving for.

If you find the information on car safety, recommended car seats, and car seat reviews on this car seat blog helpful, you can shop through this Amazon link for any purchases, car seat-related or not. Canadians can shop through this link for Canadian purchases.

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can